Beyond Musical Ranking

I’m just an academic interested in the political geography of rock music.

— Luc Ampleman

When I was recently invited by the editor of Kraków Music to prepare a column under a title which would sound like ‘The 10 Polish albums that…’, my first reflex was to answer: ‘Yes, but no!’. I guess that most popular music lovers would consider this kind of exercise not only a challenge but above all a trap! As a non-Polish enthusiast of Polish popular music (and I like to think that I rather cast the net far and wide in this matter since I love popular Polish music from Mieczysław Fogg to Behemoth) the task of selecting a few albums for a blog sounds more like a punishment than an opportunity. Secondly, not coming from the musical industry nor being a music journalist, I don’t believe I have any sound credibility. To put it forthrightly, I’m just a damn academic interested in the political geography of rock music. And let’s be honest, musicologists excepted, musical journalists will most often have this sound advantage over any scientists interested in the popular music scholarships for the simple reason that they usually have learned to listen and connect to musicians. Besides my lack of self-confidence, however, there is more; and this has more to do with a certain reluctance to rank musical acts.

In fact, if the idea of ranking albums, artists or even songs seems to be something natural, isn’t there at the same time, some act of absolute vainglory. Ranking is everywhere. it’s difficult to skim through any popular music web news or webzines without coming across with one of those long advisory lists like ‘the most influential artists of the year 1972’; ‘the ten best songs about shrimps’; ‘1000 albums you need to listen before you got hit with a burning shovel in the face by the Hulk’; ‘all the albums of John Do ranked’; or the like of ‘where to start with the back catalogue of the band No Back Catalogue’!

A musical chart is somehow a ‘political’ act, which consists of negotiating a position for someone or something.

While the ranking or advice-giving lists constitute powerful, efficient traps you must admit that you can’t not read them You might wonder if the aim of these standing lists isn’t just to start another musical world war. The result is almost always the same: someone in the comment section will start roaring ‘where is Jane Do’ album?’ or ‘this is rubbish… no Clara Schumann, no Radiohead! no Captain Beefheart, no The Plastic People of the Universe and no Lech Janerka!” or ‘what kind of idiot would forget to put and Arvo Pärt’s Te Deum?’ Well! Here we are! And don’t even think about pushing your list of the best drummers because I promise, there will be blood. All in all, at the end of this journey through the musical ranking-porn of our time, a lot of noise for little. But musical ranking like music critiques is certainly not without interests.

In a way, the most legitimate musical rankings are perhaps those shared by your friends and loved ones since they tell a story that you can re-appropriate by putting them in a context. Musical ranking also offers a sort of social view of someone’s environment. A musical chart is somehow a ‘political’ act, which consists of negotiating a position for someone or something. This is where it starts to get interesting, at least for me. That is, the political geographer in me.

A loud cacophony: political control, perceptions and rhetorical negotiations in music

Like in musical ranking, music is all about negotiating a position, be it a message, a popular stance, an image, an opportunity to be played on the radio or to be associated with a new musical genre… Being a provocative or conciliatory musician; to censure a song or not; to get on the stage or not; to write sharp lyrics or futile catchphrases; most of what is done in music is related to negotiating a position or a standing.

Like almost anything, music is political. To a certain extent, it could be considered as a field where forms of control operate through a series of interdictions and authorisations or within a blurred zone of non-authorisation and non-interdiction. Within this logical matrix all musical stakeholders from musicians, fans or song listeners, producers to musical journalists, critics and scholars, cultural influencers, muses and even policymakers, engage in the negotiation of positions. Like in musical ranking, music is all about negotiating a position, be it a message, a popular stance, an image, an opportunity to be played on the radio or to be associated with a new musical genre. Hence, musicians may want to convince an audience or a label about their popness, or they may want au contraire to defend their undergroundness, because being underground (we all know this) is always cooler than being popular. In the same way, metal bands want to make sure that their bad-ass logo will fit the semiotic of their metal subgenre. Broadcasters’ direction may also have to decide what song can be played or even put on the top of the Friday’charts as we’ve witnessed recently in Poland. From another perspective, musical critics finetune their rhetoric to show they have more credibility than the average Joe while grilling the most recent project of an artist.

Being a provocative or conciliatory musician; to censure a song or not; to get on the stage or not; to write sharp lyrics or futile catchphrases; most of what is done in music is related to negotiating a position or a standing. This is also true for music listeners for whom any musical act can be understood within a certain frame of opposites: know-unknown; like-dislike; morally acceptable-unacceptable; popular-unpopular; innovating-conventional; politically engaged-apolitical, etc.

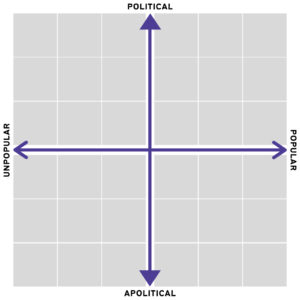

I recently had the chance (read delight) to teach a class on the political geography of popular music of the Nordic Countries. Despite the pandemic and the use of an e-learning model, to my great joy students showed a fantastic level of engagement by attending, participating and contributing in class. Among other things, I’ve asked them to reflect on the following general questions: How do musical actors (bands, artists, musical projects) negotiate (explicitly or not) their social/esthetical/political position? How do audiences rely socially on these musical acts (or not)? How does a political context shape the positioning of popular musical acts and products? While the task in hand required students to decode, evaluate and justify the political character of Nordic musical acts, I have also asked them (a few weeks before) to practice by sharing with me their understanding of the ‘political intensity and ‘popularity level’ of a few Polish bands.

The result was the plotting of a series of albums on a four-quadrant coordinate system.

An ode to joy in four quadrants

There are multiple advantages of such an exercise. Firstly, unlike the ranking systems, the cartesian coordinate system has, a priori, no dominant position. No need to browse a list that goes from the underdogs to the front-runners. No climax of enchantment or discontentment. You can read the graph from right to left, from bottom to top or by moving from the upper right to the lower left quadrant and vice versa. Of course, you can still attach emotions to the extremes of the axes of the 4-quadrant graph, like ‘execrable vs laudable albums’, but the main idea is to plot musical acts within different parameters.

This leads to the second argument in favour of the coordinate system: it scales. It is always possible to extend the diagram so that you can place lower, higher, more to the left or further to the right, any new arrival or element to add to the comparison. Here’s a tip: always place an element towards the centre of one quadrant first, knowing that there will always be someone that will find an artist less confrontational, more political or more erudite that the one you just found. Moreover, the graph can be multidimensional, that is to say, that ultimately, you can always add more dimensions, like popular-unpopular vs political-apolitical vs in-Polish-not-in-Polish-language.

Thirdly, a kind of ‘Pin the Tail on the Donkey’ adapted to popular music, it is about perception, not about appreciation. Somehow the graph itself is more interesting when filled by others than by yourself. It is less about “I’ll tell you what is worth and what is not” than about “tell me how you perceive this”. The musical coordinate system offers a map open to dialogue about how music listeners orient themselves with regards to different para-musical dimensions. The more musical acts you know, of course, the more elaborate the graphs become.

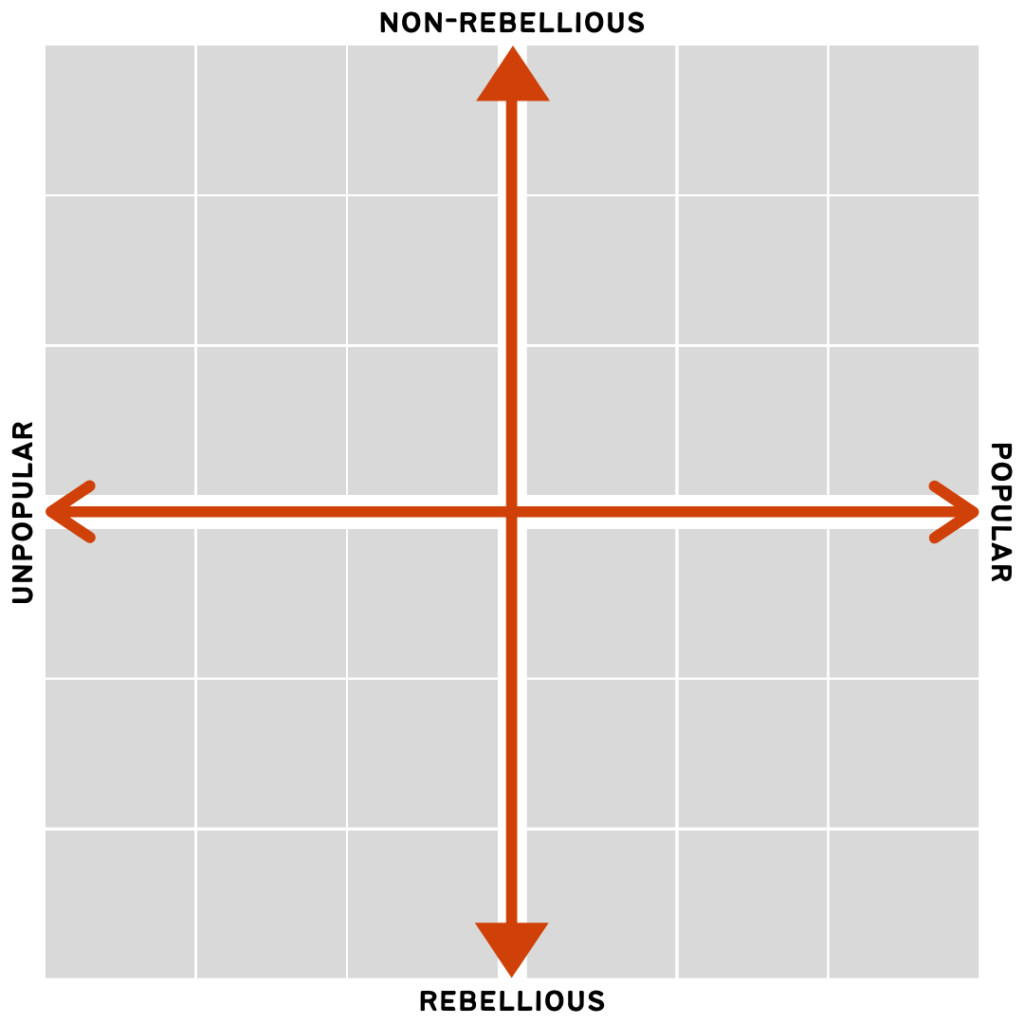

Coming back to the exercise done during my course, I was glad to discuss with students their own understanding of the ‘political intensity and ‘popularity level’ of the music. Based on the positive outcome of this experience, I decided to repeat it by asking students to classify a series of ten albums (the choice remains totally disputable) but this time according to their understanding of their ‘popularity level’ as well as their conception of their ‘intensity of rebelliousness.’ It was done as an optional, after-class activity, but it was nice to see that students stayed online after hours to complete the assignment and negotiate the positions of these albums according to their own perceptions.

The class was divided into two groups: one male and one female student clusters. Ok. Disclosure here. No! Working teams in my courses are not always, actually never, divided according to gender canons. I apologise, thus, for all the impairment I could have caused by this segregation on that Thursday morning of May. I don’t think the students held it against me and hope the readers won’t either. In any case, the result, which has no scientific value, (must it be said?) was interesting at least from an exploratory perspective.

How did my informants pin down each album on the graph?

Stay tuned and find out in the next instalment of this article. In the meantime you can give it a try in the interactive graph below.

Read Part 2 and check out the results of the experiment➞

Music Poles: 10 Albums & 5 Decades of Popular Polish Music

Timeline of selected albums.

If you are familiar with Polish popular music, you will undoubtedly recognise some of them.

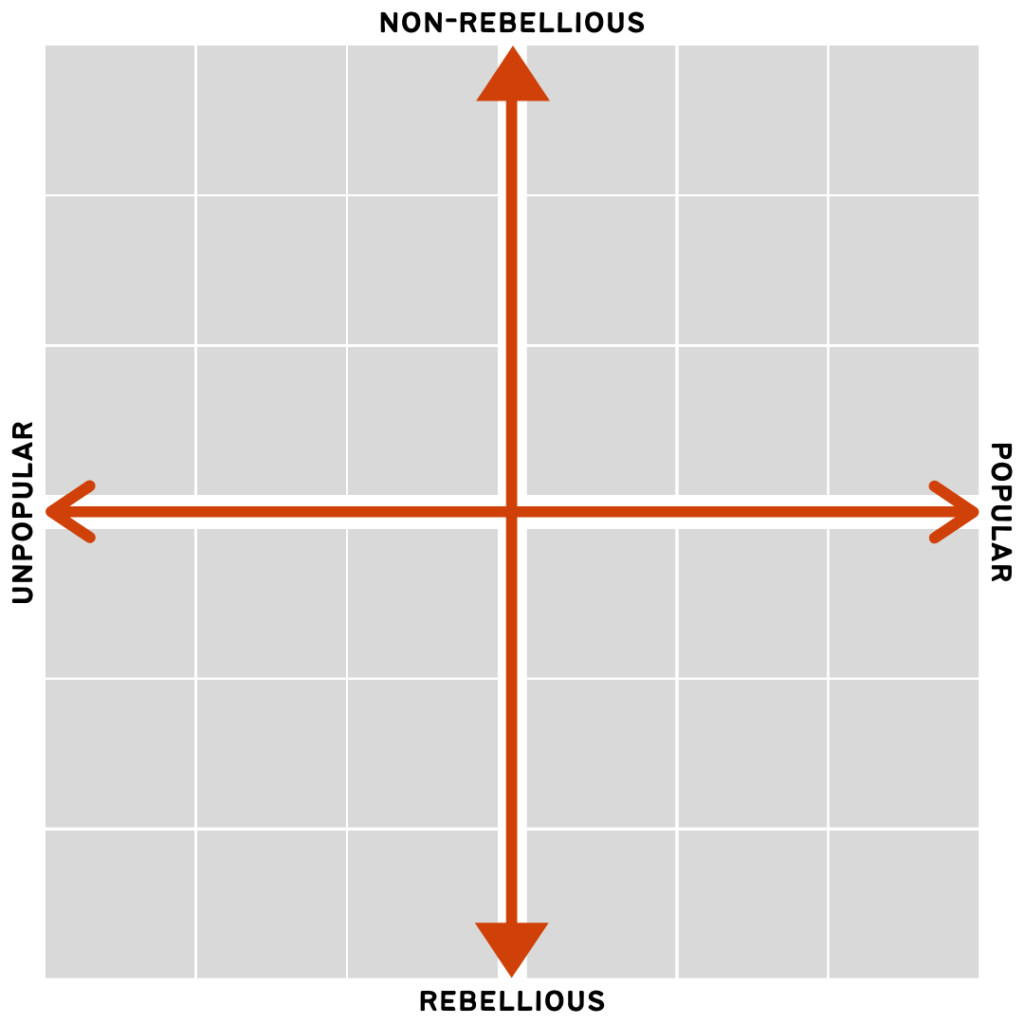

Interactive graph

Popularity & Rebelliousness in Popular Polish Music – 10 albums, 5 decades

How to use the graph

The images of the album covers are stacked on top of each other in the order given in the list.

To move a cover image, first click on it and then drag (from the middle) and drop it to the place you think represents its level of popularity and degree of rebelliousness.

Year, Album – Artist

2014, No Bad Days – The Dumplings

2005, Vabang – Vavamuffin

1996, Intro – Ich Troje

1995, Albóóm – Liroy

1990, Morbid Reich –Vader

1985, Papa Dance – Papa Dance

1984, Jeszcze Żywy Człowiek – Dezerter

1975, Cień Wielkiej Góry – Budka Suflera

1966, Malowana Lala – Karin Stanek

1955, Piosenki – Mieczysław Fogg

Comments

[…] Read Part 1 and check out the music timeline➞ Music Poles: 10 Albums & 5 Decades of Popular Polish Music […]